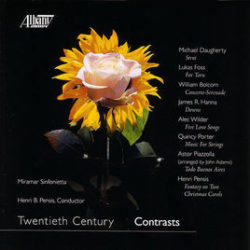

Miramar Sinfonietta: 20th Century Contrasts

Albany Records/May 2002

Strut

Miramar Sinfonietta

REVIEW FROM FANFARE MAGAZINE:

The Miramar Sinfonietta is a Milwaukee-area chamber orchestra originally founded for an occasional purpose, the recording of Henri Pensis’s Fantasy on Two Christmas Carols (this composer, 1900–58, was the father of the ensemble’s conductor). Apparently, they’ve decided to continue work with other projects, this recording being the result. Except for the final two arrangements on the program, the collection features American music for string orchestra and soloists. The Miramar plays with both polish and crackle, and their director’s programming sense is pleasing. There is much here that is engaging on a variety of levels—tuneful, sometimes challenging, eclectic but personal, never dogmatic.

Michael Daugherty’s (b. 1954) Strut (1989) joins a host of recent works that emphasize a connection to blues, funk, and R&B idioms. It’s also one of the better such efforts, with pleasingly tricky rhythmic shifts. It also has a restraint and concision one doesn’t always find in the composer’s more recent works.

Lukas Foss’s (b. 1922) For Toru (no date given) is a brief, contemplative tone poem for flute and strings that evokes the language of the late Toru Takemitsu as an homage. Foss is extremely adept with suggesting the Japanese master’s sound without literally quoting it.

William Bolcom’s (b. 1938) Concerto Serenade of 1964 shows how early the composer had already developed his trademark language of alternating between chromatic/atonal materials and more vernacular American material. Much of the music suggests the brittleness, both of sound and intellect, one hears in Stravinsky—late serial in the third movement, middle-period neo-classic in the last.

James Hanna (b. 1922) is represented by the final movement of his Fourth Symphony (1986), which is based on a hymn tune by Lowell Mason, Downs. One hears in it a sincere and gentle utterance in the manner of such American composers as Roy Harris.

The two subsequent works bespeak a conservative American lyricism of deep integrity. Alec Wilder (1920–80) was an uncategorizable composer—deeply committed to a stylish, romantic idiom that drew on jazz and popular music from mid-century. As a consequence, he is often viewed as both a “classical” composer and an elegant songwriter who has composed several cabaret standards. The 1979 Five Love Songs for horn and strings is a late work, a distillation of gestures and harmonies from the golden age of American song, a “song without words” for its age. Quincy Porter (1896–1966) was for decades associated with Yale College and wrote music of unflagging sunniness, verve, and lyricism, in a voice similar to that of his colleague Paul Hindemith (though it must be said that Porter’s tone is overall more delicate and romantic). His 1941 Music for Strings is no exception to this description.

The final two works are arrangements. John Adams made his Todo Buenos Aires for violin and string orchestra from a tango by the great Argentinian composer Astor Piazzolla (1921–1992). It is distinguished by its fanciful writing for the solo fiddle, which creates a kaleidoscope of colors, often percussive (such as pizzicato and rhythmicized scraping behind the bridge). Henri Pensis (1900–1958) was the founding conductor of the Philharmonic Orchestra of Luxembourg and a fixture in Midwest music-making, directing the Lincoln, Nebraska, Philharmonic. His Fantasy on Two Christmas Carols (again, no date) is a set of variations on the Czech “Come, All Ye Shepherds,” with “Silent Night” floating above as a descant.

Overall, a consistently intelligent and beguiling collection.

– Robert Carl