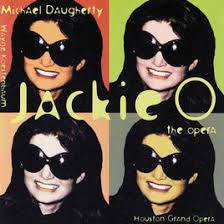

Jackie O

Decca/August 1997

Houston Grand Opera Orchestra & Chorus

Christopher Larkin, conductor

REVIEW FROM FANFARE MAGAZINE:

Topicality is royally served by a well-meshed collaboration – this opera may prove to have an enduring set of legs.

When first I heard Michael Daugherty’s Metropolis Symphony (Argo 452 103-2), I judged it a competent trifle—the very middlebrow thing to keep the lazy and ill-informed filing into the concert hall, in the event that of the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra. I mean, really—a symphony about a benday-dotted Übermensch? An especially apropos chapter of Paul Fussell’s Class, A Guide Through the American Status System is entitled “Climbing and Sinking, and Prole Drift.” The timing here is interesting. Having read the book only recently (it was published in ’83), I soon enough witnessed Fussell’s concerns intensifying by several orders of magnitude when The Princess of Wales died and the media went bananas, along with cooperatively weepy hordes; thence by easy steps to the Great Big Slap in the Head: your reporter, and quite likely you, dear reader, are creatures of the margin. I’m sorry, but there it is. Thus banished from What’s-Happening Central, we are as yet in a position to observe the means by which creative artists engage with their world. Some attach to a vision—discipline, if you wish—the pursuit of which hoists them well above the tinsel trash. Others confront it and upon it work transformations, no few of these marvelous. Witty. Profound. Exhilarating. The Paris car wreck and its media-transfixed aftermath very much in mind, I returned to Metropolis Symphony alert for secret midcult keys to prolish mysteries. Alas, nothing. Except perhaps to observe that Ferde Grofé’s spirit flourishes. Leroy Anderson’s too.

I hear Jackie O as quite another matter (pace Gramophone’s unsmitten reviewer). Here events so instantly resonate, and with such curiously timely force, one’s 60s-retro bric-a-brac fairly rattles across the étagère. And the music, moreover, is a lot more affecting, or so it appears to play, thanks in good measure to Wayne Koestenbaum’s libretto, in that the opera addresses in clever and interesting ways the culture of empty celebrity and its helium-inflated, cartoonish symbols. So let us directly to the characters and vocalists who take their parts:

Jackie, soprano Nicole Heston; Maria Callas, mezzo Stephanie Nova?ek; Aristotle Onassis, bass Eric Owens; Liz Taylor, soprano Juanita Lattimore; Grace Kelly, mezzo Joyce DiDonato; Andy Warhol, baritone Daniel Belcher; JFK’s Voice, tenor John McVeigh; and a nonvocal paparazzo, jazz tap-dancer Bruce Brown. A paparazzo! Did I not speak of resonance?! As Fort Hard Knox’s commandos will have it, tenor John McVeigh’s surname serves in our Now context as an unfortunate coincidence for which, I’ve little doubt, he has been the subject of too many sidelong glances. As to casting, one little quibble: the limp-in-life Andy Warhol as a hearty baritone—Daniel Belcher— seems to me a miscalculation. While Belcher is certainly a fine singer, my memories of Warhol are those of an ennui-beset wraith. Hardly the sort presence to set the rafters to ringing. Would an over-the-hill countertenor have been the better choice? On the other hand, mezzo Stephanie Nova?ek’s hyper-grand-operatic Callas drives that nail home. Eric Owens’ muscularly virile bass serves the coarse-grained Onassis equally well, and Nicole Heston’s Jackie sounds the perfect, soulful note. It’s an all-round excellent production and recording, and so, then, to events.

And their dramatically skillful deployment: early in the first of two acts, we are provided a several-sided insight into Jackie’s far from simple character in the exotically pungent aria “Egyptian Time,” which our eponym performs in Warhol’s loft, the Beautiful Volk in attendance, Liz and Grace among them. The temperature soon rises with the appearance of Onassis and Callas. Koestenbaum’s language is consistently engaging, often clever, with Daugherty’s aptly textured musical lines in sync with their task. When Onassis and Callas engage in a duet, “Addio del passato,” for example, the music takes on a seductive Mediterranean character that in one variant or another saturates the opera. Instantly upon what amounts to a Callas kissoff, Onassis courts Jackie (on a tangolike rhythmic footing) by inviting her in a most peculiarly hilarious gesture to see a dirty movie (I Am Curious Yellow). It goes on and on like this, with humor and pathos striking a good balance. Onassis, the very model of aggressive suitor, participates in the scene’s conclusion by enticing Jackie with “Don’t look back. / The future is about to happen. / Don’t look back . . . beyond the pale I of the camera’s flash.” Jackie’s response is a melancholy “I almost believe you .. . .” Which, of course, she shouldn’t.

The second act begins on Onassis’s kitsch-opulent yacht (e.g., whale-scrotum-upholstered barstools), replete with sycophant playboy-Greek chorus, working its way penultimately to JFK’s ghost begging forgiveness. In between, Jackie loses herself in memories (“All His Bright Light, ” a gospel-flavored, hit-quality aria), thence to a soulfully gorgeous meeting-of-souls with Callas on the island of Skorpios, where the pair is then bedeviled (Callas willingly, Jackie not) by the tap-dancing paparazzo to music rather too reminiscent of Bernstein’s showbiz-brassiest. I cannot in fairness provide a better summary without trivializing what I’ve very much enjoyed, the blatantly campy curtain-dropper included (“The New Frontier Is Here”). Enough to say that in Jackie O topicality is royally served (as it were) by a well-meshed collaboration. I shouldn’t wonder that the work proves to have an enduring set of legs.

– Mike Silverton